Last week it was reported that a fund is being set up to compensate victims and victims’ families of the Bangladesh garment factory collapse….but that some notable retailers whose garments were being made there were absent from the meeting.

Like Walmart, for example. But you already knew that Walmart is a giant dickhead among retailers, right? Low wages, union busting, decimating locally-owned businesses, obvious disregard for the well-being of the people manufacturing their products as long as they’re as cheap as possible. Even knowing all that, I was still a bit stunned to hear that they’re not at least playing the PR game and showing up at the table — you know, at least *feigning* that they care that people, who were forced to work in unsafe conditions to ensure Walmart’s clothes were being churned out as fast and cheaply as possible, actually died for this rather ignoble cause.

Ultimately, I think Walmart knows that there is only a tiny fraction of consumers who know — or care — that the demand for ever cheaper, faster, disposable goods is taking a toll on a lot of things we should value: the environment, human rights, worker safety, and a living wage, to name a few.

It was also widely reported that Canadian retailer Joe Fresh (parent company Loblaw) was among the clients of the collapsed garment factory. It’s not surprising, considering their extremely low prices.

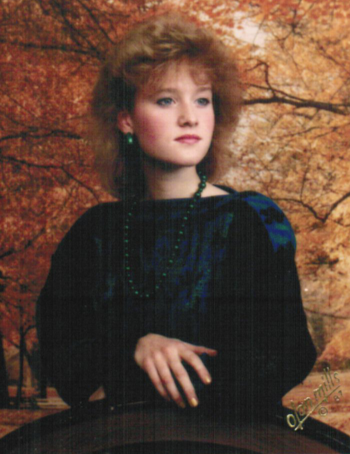

People of a certain age will realize, when they stop to think about it, that the prices of clothes have dropped significantly over the last bunch of decades. Strange, isn’t it? Hasn’t the price of most things naturally gone up over the course of decades? I remember a sweater I coveted when I was a teenager in the 80s — black with a busy green & blue motif with gold threads and big shoulder pads — that I put on layaway. (For those born after 1985, layaway is a quaint practice whereby you would put a deposit down on something you wanted but didn’t have the money to pay for all at once, and you returned each week to pay more until you had it all paid off. No credit card debt incurred. Imagine that.) The sweater was $60, which was a pretty hefty sum at the time. Nowadays that sweater would retail for probably $20.

My mother could tell you about how clothes were an even bigger investment when she was a young adult in the 50s. She saved up for clothes, and chose them very carefully, ensuring they were classic styles, well-made, and good-quality fabric so they would last a long time.

Anyway, back to that $20 sweater: how is that price possible? How can a whole garment be constructed, shipped, and sold, and all the people involved (designers, seamstresses, factory workers, shipping companies, retail workers, etc.) be paid, and a profit still be made for the parent company? The answers, I think, are obvious.

And now back to Joe Fresh. They did come to the table to meet about the compensation fund, and they did sign on to an international pact to improve conditions for garment workers since the Bangladesh factory collapse. Details of two such pacts, and which companies signed on to them, are outlined here and here. But is this enough? Should a conscientious consumer feel alright about purchasing from such a company? I have to admit, I bought a shirt from Joe Fresh today. I’m still not sure how I feel about it. I think it may feel like a dirty shirt even after it’s been laundered.

What about you? Are these issues on your mind when you shop? Can you afford to shop conscientiously? I mean, it costs a lot more for clothes that are sustainably and ethically produced. I’d love to hear your thoughts.

This topic has definitely been on my mind quite a bit in the past few months due to a) the garment factory collapse and b) the fact that I’m getting more independent in my sewing. I’ve realized exactly how much WORK it is to produce a piece of clothing, and it awes me that garments are cranked out so quickly and in such great volume for so CHEAP. I’ve also been tossing a lot of old stuff in my closet (god, I bought way too much Urban Outfitters clearance crap in undergrad) and realizing how much of it isn’t even sturdy enough to be given to charity. I think an idea is starting to germinate in my head – I want to start sewing real things that go in an actual wardrobe, instead of just fun pleated skirts and dresses.

This obviously isn’t 100% possible – I’m a poor grad student and I need to wear lots of things like suits and dress pants and other things that my sewing abilities have yet to match. For this, I go secondhand (since it’s also pretty much only what I can afford). The clothes are usually nicer quality than what you’d find at Target or Wal-Mart and I feel like I’m not directly contributing to the garment industrial complex/wastefulness of fast fashion. What’s your take on buying things that aren’t necessarily ethically sourced but are used? Thanks for this post, by the way (:

LikeLike

Thanks very much for your comment. I think buying used clothing is automatically a huge step up — you’re reusing what’s already there, instead of demanding something new be created. It’s better for the environment, for sure. And of course we can only do what we can within our budgets. It’s not feasible to expect people who are struggling to make ends meet to not shop where they can get the lowest price, so I try not to be too judge-y about Walmart shoppers. For many, though, including me, we sometimes just mindlessly buy yet another cheap item even though our closet is already stuffed. I’m shocked at how often I drop off to Goodwill a garbage bag full of clothes I don’t want any more, that are practically still new. I’ve read that charity shops like Goodwill and Salvation Army can’t even handle the amount of unwanted goods that are dumped on them nowadays. Anyway, the first step is to recognize the problem…now that we’re thinking about it, we can make better choices. (“Hi, my name is Average North American, and I’m a consumption-aholic.”) Good on you for making your own clothes!

LikeLike